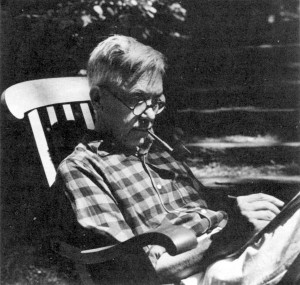

William A. Dwiggins: Master of Typography And Type Design

Who?

Why he was just a typographic tinkerer who said a lot of things:

“What any given person knows about the graphic side of advertising is limited. There is no body of tested data relating to the subject.”

“The end product of advertising is not printing—it is sales.”

“What type does the architect of advertising elect to use, and why? That question is the acolyte’s invariable first prayer for enlightenment—phrased always in one of the various voices of despair—what type shall I use? The gods refuse an answer. They refuse (sacrilege though it be to say it) because they do not know.”

It would be easy to fill this entire magazine with such excerpts since the remarks of Bill Dwiggins comprise a veritable Bartlett’s of the Graphic Arts. In fact, to demonstrate who Dwiggins was is not really necessary or even to argue but simply to quote.

What brings him to mind at this moment is the realization that it is now 17 years since his death, on Christmas Day, 1956.

Just this week I received word from Laurance Siegfried that on January 15, 1974, he will speak at the opening of the Dwiggins’ Room in the Boston Public Library. Old-timers will recall that Larry Siegfried is a renowned former editor of the American Printer and more recently is the retired head of the Graphic Arts Department at Syracuse University. As WAD’S cousin, he is in an excellent position to inform the present-day acolytes about one of the most remarkable practitioners ever to labor in the area of typographic design.

The above quotations were taken from a book, Layout in Advertising, which Dwiggins wrote while commuting between his home in Hingham and Boston, where he maintained a studio. It was published in 1928 and reprinted in 1948. Both editions are now out of print and most existing copies have been worn to a frazzle by a couple of generations of delighted owners. Nearly everyone who has ever read the book would nominate it for a Nobel Prize in the categories of literature, graphic design, or just plain common sense.

That Dwiggins approached the task of writing a manual of design with some trepidation may be noticed in the preface to this text, in which he quoted Izaak Walton. Walton wrote, in his own treatise on angling, of the difficulty of teaching anything practical in a book: “Not but that many useful things might be learned . . . but art is not to be taught by words, but by practice.”

Nevertheless WAD did teach by words by virtue of his quiet wisdom and tongue-in-cheek comments concerning many of the dogmas that have come down through a thousand texts on the subject of graphic design. The very title of the book assures the reader of its practicality. His words were buttressed, however, by the numerous little sketches placed in the margins of the book to illustrate his principles. Today it would probably be called Graphics for Advertising Typography, but—lacking the four-color reproductions of what’s hot on Madison Avenue—it might never find a publisher.

Dwiggins was just not at home in the field of advertising and promotion, but was, in essence, the Compleat Printer, covering a wider range of activity than any other noted typographer of this century.

In fact, he is collected today by such a divergent group as illustrators, calligraphers, bibliophiles. typographers, and puppeteers—not to mention those who accumulate his writings and couldn’t care less whether or not he had the ability to place the proverbial line properly on the paper.

In all of this divergent activity his talent is first class, be it satirical prose or the spine of a binding. In the latter category, a collector could easily specialize and praise the gods that publishers allowed Dwiggins the time to develop this skill into an art form. I recall spending a couple of pleasant hours working with the late George Salter at AIGA in mounting a small show of Dwiggins’ work. Salter, one of the great calligraphers, stated that WAD’S way with lettering a book title was superb and could not be duplicated by anyone, here or abroad.

No one has yet managed to publish a complete bibliography of the work of Bill Dwiggins, but I am happy to report that Dwight Agner, production manager at Louisiana State University Press, after several years of effort is currently printing what will undoubtedly become the most ambitious bibliography yet written, in his tiny Press of the Night Owl.

As a book designer, Dwiggins produced over 500 volumes of trade editions for one publisher alone (Alfred A. Knopf). In addition he made numerous designs for other houses, including the Limited Editions Club.

Next to book typography, he is known for the types which he designed for Mergenthaler Linotype Co., which included one of the most widely used styles ever produced in this country—Caledonia. This design represented a new approach to that 19th century standard, Scotch Roman. Caledonia is a perfect type for the typography of the book. having excellent weight and a high degree of legibility besides being free from annoying characteristics.

Another highly regarded Dwiggins’ type is Electra, a type in the modern classification but lacking the mechanical features of the Bodoni-Didot style. The first type drawn by Dwiggins was the sans serif Metro (1929), which was the Linotype entry into the serifless derby of the Twenties. I have stats of WAD’S first drawings for Metro, and it is a far different type than the face finally chosen for production, which was particularly successful in the newspaper field. Dwiggins, as a humanist, naturally enough was drawn to a sans serif with a classical base, rather in the manner of Hermann Zapf’s Optima design of the 1950’s. It would be interesting to see the correspondence between Hingham and Brooklyn at that time!

To many typographers, Dwiggins was at his most unique in his production of ornaments, to which he brought a style which was strictly his own, and whimsical in the extreme. Here is a field in which was inimitable, and which lent an individualized style to his work which has never been approached, providing the instant recognition upon which his reputation was built.

Will Dwiggins seems to me to be one of the finest graphic artists of our time. For today’s younger typographers there is much to be gained by a study of his 51-year career. This is true particularly at a time when there appears to be a continuing search for ways and means by which to emerge from the sterility of overuse of the superabundant sans serif types and an increasing dependence upon mechanical grid systems in design.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the December 1973 issue of Printing Impressions.