Old Stand-By Faces Outlive the Trends

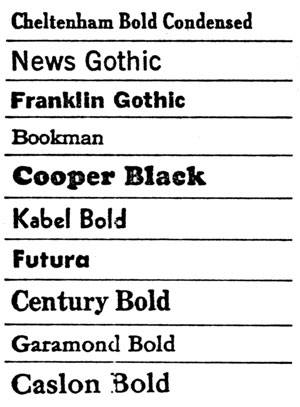

In a recent issue of the printing trade periodical, full-page advertisements use the following types for display:

Cheltenham Bold Condensed

News Gothic

Franklin Gothic

Bookman

Cooper Black

Kabel Bold

Futura Heavy

Century Bold

Garamond Bold

Caslon Bold

So what is changed, typographically, in the last 40 years? All of these ads could have been said by any typesetter in 1928, although it may be noted that some of the accompanying ads in the same magazine showed such postwar types as Optima, Univers, Craw Modern, etc. Of course, notably missing were Boul Mich, Broadway, Novel Gothic, and such other favorites which could have been expected to be encountered in the Twenties.

What Are the Trends?

Since this particular magazine is fairly typical of the trade press in the United States (not limited to printing), what is a typographer to deduce if he is attempting to seek out trends in type utilization? The former reminded by someone that trade publications do not represent the acme of typographic perfection, I had better state than my observations are not limited to the source, fast as it is statistically in its annual share of the advertising dollar.

Turning to a consumer magazine, represented by a current issue of The New Yorker, it is equally evident hereto, the old stand-by types are the most popular. Out of some 55 full-page ads, just 18 had their display line setting typefaces which have become available since 1950. Even here the degree of originality is questionable, as five as were set in the renovated topics represented by Helvetica, Folio and Univers. One ad was set in Clarendon, basically a mid-19th century style, and five are composed in a hairline sans serif reminiscent of Futura.

Geometric Sans Serif

The only trend noticeable is perhaps represented by this last group, although reality it probably at best represents but a blip on a trend–the comeback of the geometric sans serifs of the Futura pattern. This in itself is undoubtedly a negation prompted by an overlong exposure to the gothic types.

Ever since the re-introduction of Venus by the Bauer Type Foundry about 1952, there is been a proliferation of gothics, most of them revivals. There was a momentary dip in their popularity about 1956 when the century-old Clarendons were spotlighted, but they came back strongly following the arrival of the “integrated” gothics (Univers, Folio, Helvetica) in the Sixties.

During the last year some typographers, jaded by the everlasting look-alike quality of promotional printing, have been experimenting with the geometric sans serifs, notably Kabel, which was designed by Rudolph Koch in 1926, and Futura, of the same period, drawn by the architect Paul Renner.

Kabel, with its unique (for a geometric sans serif) lowercase “e” and “g” seems to fill the bill of being different without being too great a departure from the monotone form of the great revived gothics. In the case of . . .

[missing copy . . .]

It may be that such practices represent the final expostulated in of the trend that began a year or so ago of Futura, the greatest interest seems to lie in the lightest weight available. Further, most of the designers using the style jam the letters together and in many instances overlap them. A further, and more stream, variation is to distort around letters in addition to the jamming. All of this is easily accomplished with the photographic typesetting devices and by process-lettering techniques. Into many cases, the end result is virtual illegibility.

[missing copy . . .]

compressing the space between letters. It’s hard to see that it can go much further. Even at that, it has been done before, the obvious precedent being the incised lettering on buildings and monuments. There must also be many typographers of long experience who can recall earlier love affairs with Huxley Vertical and Bernard Fashion, some 30 years ago.

I don’t wish to leave the impression that there are no imaginative designers on the contemporary scene. Anyone who looks at the exhibitions of promotional typography can readily ascertain that there are many sparkling pieces being hung by juries charged with the responsibility of presenting meaningful examples of first-rate design. But as anyone who has served on a committee to judge a show must acknowledge, and appalling number of “instant reject” pieces turn up his entries.

Trends Not Apparent

The creative effort which is presently being channeled into the production of promotional material such as posters, billboards, point-of-purchase displays, direct mail advertising, etc. is simply not in evidence in the advertising pages of many of the trade and consumer periodicals. It therefore becomes increasingly difficult to discern trends in type used on typographic design from the investigation of such sources.

Outside of the great increase in the use of process color and more creative photography, there is very little difference between the current material and that which appeared in magazines 20 or more years ago. Possibly part of the problem is the birth of distinctive new type designs. Those types which are outstanding quickly become the victims of overuse and thus are subjected to a shortened lifespan. That part present find it necessary to rely upon the old stand-by faces.

Another factor, unquestionably, is that we are in an era of technological transition. The type founders presently engaged in the production of metal types are concerned about their ability to enlarge their markets in the face of competition from the manufacturers of photo typesetting devices. There naturally reluctant to become involved in large development expenses for new designs, since all too frequently for new types are pirated by those of their competitors were not particularly ethical in their business practices.

Reasonable forecasts about typographic trends, then, is virtually impossible. Perhaps, in this momentary vacuum, the typographer can bend every effort to follow the advice of the late T.M. Cleland, who stated, “Typography, I repeat, is a servant—the servant of thought and language to which it gives visible existence.”

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the April 1969 issue of Printing Impressions.